Conventional Wisdom: Analyzing the Causes of the Great Depression

The Keynesian Perspective: Demand Deficiency and Government Inaction

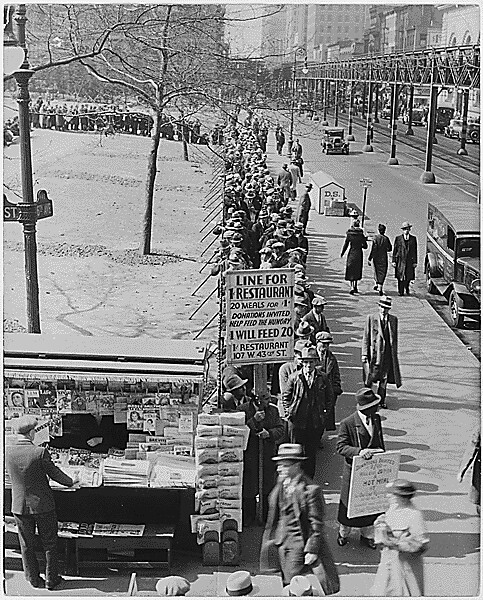

John Maynard Keynes, a prominent economist, offered an influential view on the causes of the Great Depression. He argued that the root cause was a significant deficiency in demand. According to Keynes, when the stock market crashed in 1929, consumer confidence plummeted, leading to decreased spending and investment. This reduction in demand resulted in widespread unemployment, with the rate soaring to 25% by 1933. Keynes criticized the government’s inaction, suggesting that fiscal stimulus was necessary to boost demand and pull the economy out of the depression. He believed that increased government spending could have mitigated the effects of the downturn, a theory that later influenced the New Deal policies of the 1930s.

Monetary Missteps: The Federal Reserve’s Role

The Federal Reserve’s policies in the late 1920s and early 1930s also played a crucial role in deepening the Great Depression. In an attempt to curb the stock market speculation, the Fed raised interest rates in 1928, making borrowing more expensive. This decision slowed down economic activity even before the crash. After the crash, instead of providing liquidity to struggling banks, the Fed tightened the money supply, a move that many economists argue exacerbated the banking crisis and deflationary spiral. By 1933, the money supply had contracted by nearly a third, significantly worsening the economic situation.

International Disharmony: The Impact of Global Debt and Trade Wars

The international landscape also contributed to the severity of the Great Depression. In the aftermath of World War I, European countries were heavily indebted to the United States. The U.S. insistence on debt repayment strained international relations and stifled economic recovery abroad. Additionally, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which raised tariffs on thousands of imported goods, triggered retaliatory tariffs from other countries. This trade war reduced global trade by about 50%, further depressing the world’s economies and deepening the global depression.

Analyzing the Great Depression Through the Austrian School Lens

Austrian Economics: A Primer

The Austrian School of Economics, with its emphasis on individual choice and spontaneous order, offers a distinct analysis of economic downturns. Central to this perspective is the belief in the market’s ability to self-regulate, given the absence of government intervention. Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, prominent figures of this school, argued that the business cycle results from government-induced distortions in the market, particularly through monetary policy and credit expansion. They posited that the artificial lowering of interest rates leads to malinvestment, where resources are misallocated into unsustainable sectors.

The Austrian Diagnosis: Causes of the Great Depression

From the Austrian viewpoint, the Great Depression was not merely a consequence of market failure but a result of systemic malinvestments fueled by the Federal Reserve’s easy credit policies during the 1920s. This school of thought highlights how the Fed’s efforts to stimulate the economy through low interest rates led to a speculative bubble, particularly in the stock market and real estate. When the bubble burst in 1929, it revealed the extent of the malinvestments, leading to a painful but necessary economic correction. The Austrians argue that the subsequent interventions by the government and the Fed, aimed at preventing the economy’s natural adjustment process, only prolonged the depression. For instance, the Fed’s initial response to the crash was to increase the money supply, a move that Austrians believe delayed the necessary liquidation of bad debts and malinvestments.

The Austrian School’s analysis extends beyond the immediate causes of the Great Depression to critique the policy responses that followed. They contend that measures such as the New Deal, while well-intentioned, interfered with the market’s self-correcting mechanisms. By artificially inflating wages and prices, and by increasing government spending, these policies, according to Austrian economists, exacerbated and prolonged the economic downturn.

The Aftermath and Legacy of the Great Depression

Policy Responses and Their Implications: An Austrian Critique

In the wake of the Great Depression, the U.S. government, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, implemented the New Deal—a series of economic programs aimed at recovery, reform, and relief. While these policies sought to stabilize the economy and provide jobs, the Austrian School views them critically. They argue that such interventions prevented the necessary market corrections by propping up failing industries and artificially inflating wages and prices. According to Austrian economists, these actions prolonged the depression by delaying the adjustment processes that would have restored economic equilibrium. For instance, the National Recovery Administration (NRA), established in 1933, set minimum wages and prices, which, from an Austrian perspective, interfered with the free market’s ability to correct itself.

Lessons Learned: Applying Austrian Insights to Modern Economics

The Great Depression and the Austrian critique of the policy responses offer valuable lessons for contemporary economic policy. One key takeaway is the importance of allowing markets to adjust naturally to economic shocks. The Austrian School’s emphasis on the dangers of excessive credit expansion and government intervention resonates in today’s debates over monetary policy and economic recovery strategies. For example, the 2008 financial crisis reignited interest in Austrian economics, as it highlighted similar issues of malinvestment and the potential pitfalls of aggressive monetary easing by central banks. This perspective suggests that long-term economic stability requires policies that foster sound money, minimal intervention, and respect for the market’s self-regulating mechanisms.

The legacy of the Great Depression, viewed through the Austrian lens, underscores the complexity of economic crises and the responses they necessitate. It challenges policymakers to consider the unintended consequences of intervention and the value of economic freedom. As we navigate modern economic challenges, the insights from the Austrian School offer a cautionary reminder of the need for prudent economic management and the risks of straying too far from market principles.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Austrian insights on the Great Depression offers a unique perspective on one of history’s most devastating economic downturns. By examining the causes, responses, and aftermath through the Austrian lens, we gain a deeper understanding of the intricate dynamics of economic crises. This exploration not only sheds light on the past but also provides valuable lessons for the present and future. It underscores the importance of market mechanisms, the dangers of excessive intervention, and the need for sound economic policies. This perspective enriches our understanding of economic history and policy, encouraging a balanced approach to managing economic cycles.

Leave a Reply